Neoconservatism:

Chapter 3: Sending Signals part 2

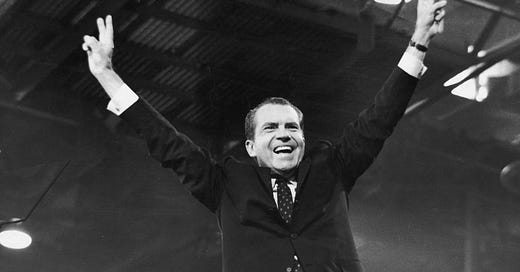

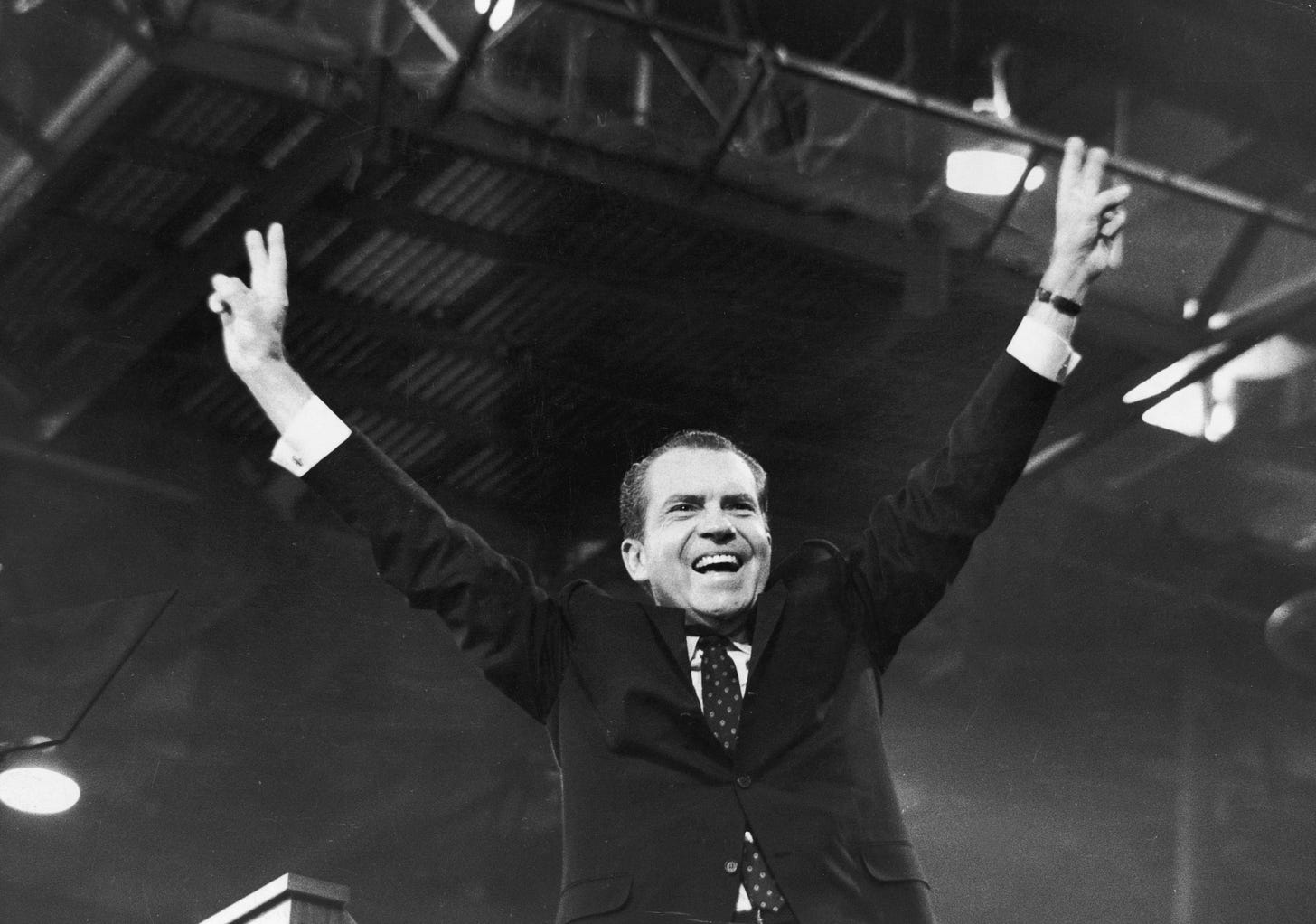

I’m back and let’s just get right into it. Last week left off, Nixon left the ABM (Anti-Baltistic Missle defense program) to Scoop Jackson and his buddies. So, let’s see what happens next.

Before the ABM battle truly began, Nixon had his first real and clear conflict with the right. About the long-running feud over U.S. Intelligence estimates of Soviet power. For a while, the RAND Corporation experts, working for the Pentagon, had characterized the Soviet missiles as a threat to the United States. However, the CIA and State Department offered lower estimates, painting a much less forbidding picture of a Soviet threat. The “low-ballers” believed the Soviets would cease production once they caught up to the U.S. whilst the “high-ballers” believed the Soviets would continuing building until they had the missile advantage.

During Johnson’s presidency, Kissinger and Kraemer were high ballers, charging that the CIA’s less alarmist advice refused to take into account “Soviet objectives and strategies.” At a press conference, Nixon confounded the high estimators/ballers. He was asked whether “the U.S. would seek parity or superiority in nuclear arms,” Nixon responded that he would pursue “sufficiency,” a vague term he didn’t define or quantify and Kissinger soon fell in with that sentiment.

Kissinger changing his tune on an important topic clearly demonstrates how quickly he arrived at the understanding that he could amass substantial power only if Nixon trusted and relied on him. This meant furthering Nixon’s goals however he could, despite disagreeing.

“Idealism is difficult to maintain when when an ambitious man is close enough to power to feel its thrill, and harder still when the fount of that power is an ultra-pragmatist”

Kissinger describes in his memoirs how he was in the early months on Nixon’s presidency “naive” when it came to some aspects of his role as national security advisor, and “ignorant of the ways of Washington.” Despite a decade of consulting executives, Kissinger was not really comfortable as a manager of bureaucrats. So, he turned to Kraemer’s other protégés, 44 years old Al Haig. Only a year younger than Kissinger; though a dutiful aide-de-camp, he considered him more a peer than subordinate, and well beyond Kissinger in bureaucratic know-how.

The complicated interplay between Kraemer’s protégés, would continue throughout the Nixon years. Caught between their idealistic tutor and pragmatic boss, they were constantly readjusting the balance of their loyalties—to Nixon, Kraemer and his philosophy, and to one another.

As Kissinger warmed to the prospect of wielding the president’s power as his own, Haig—not yet as close to Nixon—remained closer to Kraemerite hawkishness. This continued to play out in the six-month sage of the “actual or feigned” actions memo that Nixon and Kissinger had requested of Wheeler in their January meeting. This memo contained recommendations by Wheeler’s staff that had been given to Laird, who sent them to Kissinger to forward to Nixon. Haig, an army colonel with no stars, saw the memo first, and recommended to the National Security Advisor (NSA) that the memo be bucked to the four-star general for more work, because the suggestions were poor. The biggest “feigned” action relied on staged events including a “technical escalation of war” by nuclear means, which meant putting America’s forces on DEFCON 3.

At 7:20 a.m. on the morning of April 15th, 1969, Kissinger awakened President Nixon by phone with bad news: a few minute earlier, forty-eight miles east of the Korean peninsula North Korean MiGs had shot down an unarmed and unescorted U.S. Navy EC-121 reconnaissance plane. All thirty-one men aboard were missing, presumed dead. This was the administration’s first foreign policy crisis. “We were being tested.” Nixon wrote in his memoir. Kissinger, in his, suggests that Nixon thought the strike by a Communist power was a signal for him personally, to test his resolve.

Kissinger assigned the task of detailing the military options to Haig, Halperin, and Lawrence Eagleburger, and he also consulted Fritz Kraemer. Haig May have also talked with Kraemer about the matter, as he did often in those days. Both protégés were mindful of the relevance of Kraemer’s ideas in the importance of acting decisively and quickly in such crises; they knew Kraemer’s view that an absence of immediate and forceful action would amount to an American moment of “provocative weakness.” But the U.S. might not be in such a shape to effectively retaliate.

The first reaction from the JCS was to alert army units in S.K., to prepare jet units to fly in, and to ready several large ships from Vietnam and Philippines to travel westward. However, in reviewing their options (K)issinger and (N)ixon were chagrined to discover that the only ready U.S. plans for action were for repelling a NK invasion of the South. Haig’s group showed (N) ten military paths forward ranging from seizing a NK ship at sea to shore bombardment to an air strike against the base from which the MiGs had flown from. Of these, (N) and (K) favored an aggressive but proportional military response—the raid against the MiG base. According to (N), (K) argued that “a strong reaction from the U.S. would be a signal that for the first time in years the U.S. was sure of itself. It would shore up the morale of our allies and give pause to our enemies.” Kraemer would have said the exact same thing and (N) agreed.

However, a dose of realism would puncture that ballon. U. Alexis Johnson, an assistant secretary of state, pointed out that “when NK (North Korean) radar picked up our planes coming in for the attack, they might easily conclude that we launched a general attack and consequently put into motion all their well-prepared plans for attacking the south. That would unleash a much larger war, for which we were not prepared.” Kissinger was unbothered by the warning and said if things escalated we could bomb them into submission and said he’d be willing to use nukes. No one else was. Nixon hesitated however. Secretary of State Roger’s recommended that Nixon do little in response. “The weak can be rash; the powerful must be restrained,” Rogers said.

Roger’s formulation was the exact opposite of Kissinger’s Kraemerite proposal. At a press conference on the morning of April 19th Nixon conveyed a more bellicose stance than the one he adopted. Saying he dispatched ships to the Sea of Japan, hoping to create the impression in the American public’s mind—and in NK’s—that he was considering a carrier-based strike, despite ruling out the option. The incident faded from headlines without any significant American response. However, the administration’s handling of the incident sent the very message to both Anti-Communists and America’s enemies that Kraemer and his cronies feared.

Meanwhile, in an article on the front page on May 9th, 1969, NYT military correspondent William Beecher partially revealed secret bombings of Cambodian sanctuaries of the NV. Beecher was pro-military same with most of the Pentagon beat reporters, and very well versed in military affairs. Kraemer trusted Beecher not to reveal any secrets he might’ve picked up that might be detrimental to U.S. interests. The White House reacted sharply to the report, despite being incomplete and did not mention deception. Nixon was preparing the final stages of his major address to lay out peace plans for Vietnam, he was not planning to reveal while his government was talking peace, it was bombing NV, SV, Laos, and Cambodia. Should news of the bombing get out his peace plans would be considerably less credible. It would reinvigorate anti-war forces, awaken Congress from its slumber, and convince the Soviets that they had little incentive to respond to Nixon’s overtures. His honeymoon would come to an abrupt end.

So, who was the leaker? One such candidate was Morton Halperin, who had been Beecher’s roommate at Harvard and stayed a close friend. On the day the Times story ran, Kissinger cut off Halperin’s access to classified material and discussed with J, Edgar Hoover a wiretap on Halperin’s home phone. Hoover said he would arrange the tap if Attorney General Mitchell authorized it, and Mitchell soon complied. According to the Hoover memo, Kissinger also wanted the tap for a more personal reason: to “destroy whoever did this … no matter where he is. To NSC staffers were also tapped and on Laird’s chief military aide, Colonel Robert Pursley, whose frequent questioning of (K’s) demands (as conveyed by Haig) had made him a thorn in the sides of both W.H. aides. However, nothing of value turned up.

Even so, Kissinger, with the input from Haig, had the FBI place wiretaps on a growing list of targets in the media, Pentagon, and the NSC. One (K) aide was forced to resign, because he was heard speaking to a reporter, though the aide was never indicted. However, this was not the only message transmitted by the W.H’s. frantic reaction to the Beecher leak. The NV already knew their Cambodian sanctuaries were being bombed, but hints of the White House’s efforts to stop the leaks about the Cambodian bombings confirmed their sense that Nixon’s was scared of reigniting anti-war protest on the home front. And since no ground troops were sent in to clear out the bombed sanctuaries, the entire bombing campaign and effort to cover it up— constituted a spectacular display of American weakness. Kraemer’s predictions were coming to pass. After conferring with their Chinese backers, NV’s leaders reaffirmed their determination to stay the coarse.

And so, by the late Spring of ‘69, the boast of Nixon’s and Kissinger had made privately to themselves and others—that they would end the war in Vietnam in 100 days of taking office—was dust. In trying to project strength, Nixon and Kissinger had instead made exactly the mistake Kraemer had warned them against: They had played a provocative weakness.

Thank you all for joining me today and reading my ramblings. I think what I’m going to do next is finish the book, then come back and finish this series. Anyways. Take care and have a bless day!

Interesting as always. I think there are too many points being covered at once although the focus isn't Nixon so it makes sense. I would sharply disagree that responding to the Viet Cong's occupation of Cambodia was a sign of weakness however. I think that is one of those ideas that the left has cemented that falls apart when the truth catches up. The main point was to give the South Vietnamese military concrete training, it did, and it was against a legitimate military target. Nothing to be protested and Nixon's re-election shows that any public hostility was fake and perhaps even gay. Still enjoyed the read however.